Carbetocin versus oxytocin for prevention of postpartum hemorrhage in obese nulliparous women undergoing emergency cesarean delivery

Manal M. El Behery1, Gamal Abbas El Sayed1, Azza A. Abd El Hameed1, Badeea S. Soliman1, Walid A. Abdelsalam1, and Abeer Bahaa2

1Obstetrics and Gynecology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Zagazig, Egypt and 2Obstetrics and Gynecology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Suez Canal University, Ismailia, Egypt

Abstract

Objective: To assess and compare the effectiveness and safety of single IV polus dose of carbetocin, versus IV oxytocin infusion in the prevention of PPH in obese nulliparous women undergoing emergency Cesarean Delivery.

Methods: A double-blinded randomized-controlled trial was conducted on 180 pregnant women with BMI430. Women were randomized to receive either oxytocin or carbetocin during C.S. The primary outcome measure was major primary PPH 41000 ml within 24 h of delivery as per the definition of PPH by the World Health Organization Secondary outcome measures were hemoglobin and hematocrit changes pre- and post-delivery, use of further ecobolics, uterine tone 2 and 12-h postpartum and adverse effects.Results: A significant difference in the amount of estimated blood loss or the incidence of primary postpartum haemorrhage (41000 ml) in both groups. Haemoglobin levels before and 24-h postpartum was similar. None from the carbetocin group versus 71.5% in oxytocin group needed additional utrotonics (p50.01). The uterine contractility was better in the carbetocin group at 2, and 12-h postpartum (p50.05).

Conclusions: A single 100-mg IV carbetocin is more effective than IV oxytocin infusion for maintaining adequate uterine tone and preventing postpartum bleeding in obese nulliparous women undergoing emergency cesarean delivery, both has similar safety profile and minor hemodynamic effect.

Keywords

Carbitocin, emergency C.S., obesity, oxytocin, postpartum hemorrhage

History

Received 7 December 2014 Revised 18 March 2015 Accepted 20 April 2015 Published online 6 May 2015

Introduction

The risk of postpartum haemorrhage is much higher for women undergoing Cesarean section [7], particularly in developing countries, where the majority of operations are carried out as an emergency procedure [8]. Maternal obesity is associated with an elevated risk of intrapartum cesarean section, mainly due to reduced uterine contractility culminat- ing in failure to progress in labor [9–11].

Up to date, which uterotonic agent suitable for prophylac- tic use is being debated and literature lacks of clear endpoints on this item. The most routinely and widely used uterotonic agent for preventing postpartum haemorrhage is oxytocin, but it only has a half-life of 4–10min [12,13]. So, it must be administered as a continuous intravenous infusion to achieve sustained uterotonic activity, which is inconvenient and makes dosing errors a possibility. Another agent is syntome- trine (a combination of oxytocin and ergometrine). When compared with oxytocin alone, syntometrine had a statistic- ally significant reduction in the risk of PPH [14]. However, adverse effects of nausea, vomiting and hypertension are higher in women receiving syntometrine because of the ergometrine component.

Carbetocin is a long-acting synthetic octapeptide analogue of oxytocin with agonist properties. Like oxytocin, carbetocin binds to oxytocin receptors present on the smooth muscula- ture of the uterus, resulting in rhythmic contractions of the uterus, increased frequency of existing contractions and increased uterine tone. Several studies have shown the efficacy and safety of carbetocin in various clinical scenarios. A single intravenous dose of 100 lg of carbetocin has been shown to be as effective as a single dose of oxytocin in preventing intra-operative blood loss after Cesarean section [15] Another study reached a similar conclusion when a single-dose carbetocin was found to have similar efficacy to a 2-h infusion of oxytocin in controlling intraoperative blood loss after placental removal [16]. No studies till now assessed the effectiveness of carbitocin in women undergoing emer- gency C.S.

We conducted this double-blinded randomized study to assess and compare the effectiveness and safety profile of single IV polus dose of carbetocin, versus continuous IV oxytocin infusion in the prevention of PPH in obese nulliparous women undergoing emergency cesarean Delivery.

Patients and method

This double-blinded randomized-controlled clinical study was conducted in Zagazig University maternity hospital, and Suez Canal University Hospital from 1 January 2013 to 31 June 2014.

About 180 women were included in this study. All were obese with BMI430. Maternal body mass index (BMI) (kg/ m2) calculated using maternal height and weight measured to the nearest centimeter and kilogram, respectively, at time of admission to labor word. The participants were enrolled in the study after fulfilling the inclusion and the exclusion criteria; a written informed consent was taken from eligible women on admission. The study protocol was approved by IRP of Zagazig University hospitals.

Inclusion criteria were nulliparous with a singleton preg- nancy, Gestational age 37 weeks±0 day or greater (gesta- tional age was recorded according to the last menstrual period and was confirmed by ultrasound). In case of discrepancy, an ultrasound early in pregnancy 5–14 weeks or before 20 weeks gestation was taken as the actual gestational age.

Exclusion criteria were multigravida, malpresentation. This allowed reduction of confounding factors to a minimum. Women who delivered vaginally or by elective C.S. were excluded as well, thus only women who undergone emergency Cesarean section was included in the final analysis.

Emergency cesarean was defined as delivery because of an emergency situation in the active phase of labour (e.g. failure to progress, obstructed labour and fetal distress) when the cesarean section was performed having not been previously considered necessary.

Patients were then randomized to receive either two ampoules 20 IU oxytocin (Syntocinon; Alliance, Chippenham, UK) in 1000 ringer lactate as IV drip or 100 lg carbetocin diluted in 10 ml of Ringer’s lactate solution (Pabal; Ferring, Langley, UK). The study medication (carbetocin or oxytocin) was administered by the anesthetist only after delivery of the infant has been completed preferably before placental removal.

The randomization protocol required a designated member of the staff to open a sealed, opaque envelope containing a computer generated code randomizing the Patient into one of the two groups. This code was used to identify the patient;neither the patient nor the investigators knew which drug was used. The codes were broken only after the study was finished and all the information were tabulated and analyzed, thus avoiding detection bias.

As two drugs are administered differently, a double dummy system for administration was used. The randomiza- tion assigned the patient to one of the two following protocols.

Protocol A (carbetocin + placebo)

Carbetocin 100lg+Ringer’s lactate solution 10ml injected directly into the vein over 2 min. Ringer’s lactate solution 4 ml in 1000ml of Ringer’s lactate solution, administered intra- venously at a rate of 125 ml/h.

Protocol B (oxytocin + placebo)

Ringer’s lactate solution 11 ml injected directly into the vein over 2min. Oxytocin 20U diluted in 1000ml of Ringer’s lactate solution, administered intravenously at a rate of 125 ml/h.

The primary outcome measure was major primary postpartum hemorrhage defined as blood loss 1000ml within 24h of delivery as per the definition of PPH by the World Health Organization [17]. This clinically relevant amount was selected as a lesser blood loss of between 500 and 1000 ml is not uncommon and is not associated with adverse outcomes in the majority of healthy women [18]. Blood loss was estimated by the surgeon in the usual way (visual estimation, number of used swabs and amount of aspirated blood [15]).

Secondary outcomes were hemodynamic effects of carbe- tocin and oxytocin, in terms of impact on the blood pressure (BP) suddenly after the injection, incidence and amount of blood transfusion, hemoglobin and hematocrit changes by comparing the haemoglobin concentration on admission with the measure at 2 and 24h after delivery, the use of further ecobolics, uterine tone and adverse effects 24h postpartum. Uterine tone was evaluated by palpation and describing the resistancy as soft or well contracted Administration of additional oxytocics will be the decision of the investigator if blood loss exceeds 500 cm3 with or without hypotension, poor uterine tonicity or tachycardia.

Statistical analysis

For a power analysis of 90%, the study needed of 90 patients in each group. Data were processed using SPSS version 15 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Quantitative data were expressed as means±SD, while qualitative data were expressed as num- bers and percentages (%). Student’s t test and ANOVA test were used to test significance of difference for quantitative variables and chi-squared was used to test significance of difference for qualitative variables. A probability value of p value 50.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 280 obese nulliparous women with singleton pregnancy were initially recruited for inclusion in this study. One hundred cases were excluded (4 had congenital fetal anomalies, 7 cases had placenta previa, 5 cases were diabetic, 8 had hypertension, 9 had preeclampsia, 3 cases were cardiac, 28 cases needs general anaesthesia, 17 cases delivered vaginally and 19 cases delivered by elective cesarean section). Thus, 180 women formed the final study group and were included in the final analysis.

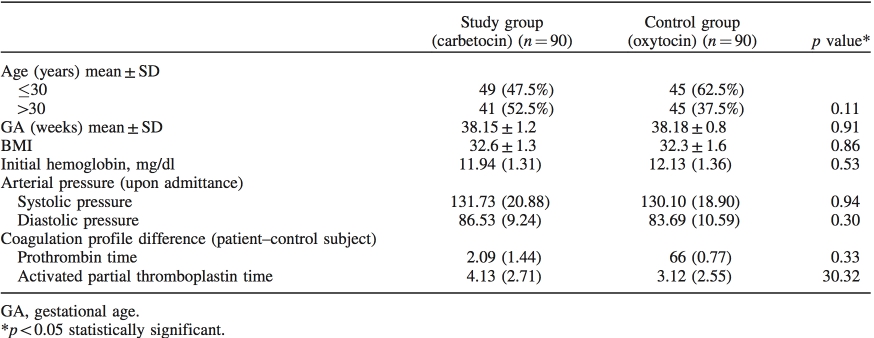

Table 1 shows no statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding age, gestational age, BMI, initial hemodynamic or laboratory parameters.

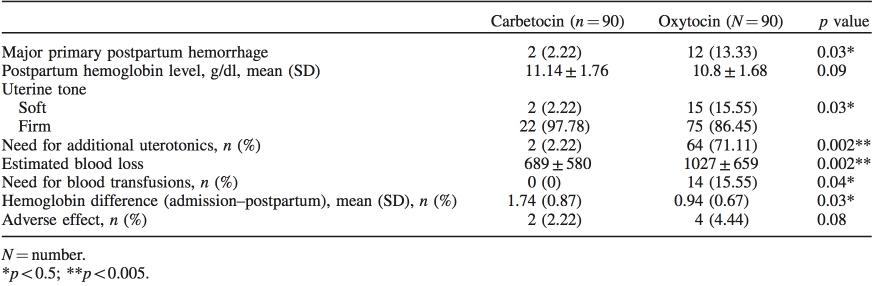

Table 2 shows the primary outcome a significant difference in the amount of estimated blood loss and in the incidence of primary postpartum haemorrhage (41000 ml) in both groups (p50.05). Regarding the secondary outcome, in both study groups haemoglobin levels before and after 24 h from delivery was similar, confirming no significant difference in the level of blood loss none from the carbetocin group versus 85% from the control group, needed additional oxytocics (oxytocin, methylergometrine, rectal suppositories of misoprostol). Therefore, significantly more women required additional uterotonic agents in the oxytocin group (p50.01). There was a significant difference in the uterine tone. The uterine contractility was better in the carbetocin group at 2, and 12 h after cesarean section, and the difference was statistically significant (p50.05).

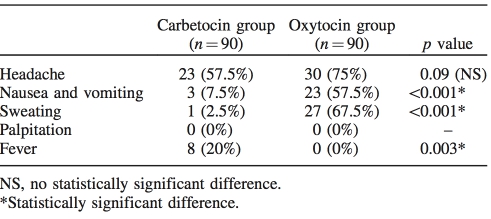

Table 3 shows that nausea, vomiting and sweating were reported more in oxytocin group patients with statistically significant difference, while low-grade fever was higher in carbetocin group patients.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of carbetocin and oxytocin groups.

Table 2. Primary and secondary outcomes measures.

Table 3. Side effects and postpartum complications in carbetocin and oxytocin groups.

Discussion

An increasing body of evidence suggested that obesity predisposed women to complicated pregnancy and increased obstetric interventions. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind comparing efficacy and safety carbetocin with oxytocin in emergency cesarean sections with two identifiable risk factors for primary postpartum hemorrhage namely obesity and null parity. We specifically choose this group of women as both nulliparity and obesity separately or in combination increase the women risk of having PPH [19]. It is also well established that obese women have a higher rates of cesarean section, especially emergency intrapartum cesarean section [20]. In one study [21], this mode of delivery has been confirmed to be associated with the highest rates of PPH among the whole study population, and the investigator found that women who had a cesarean section had a 70% increase in risk for PPH. Challenging surgery in obese patients is associated with prolonged operative time, and consequently with increased blood loss [22].

Another independent risk factor is null parity, because nulliparous women comprise a large sub-group of the birthing population nowadays they were shown to have an elevated rates of PPH compared multiparous [6–8]. In a study from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway, the risk for severe postpartum hemorrhage, which was defined as a visually estimated blood loss of 1500ml within 24h after delivery or the need for a blood transfusion after delivery, was increased among primiparous women with spontaneous onset of labor and operative vaginal delivery (OR 1.40, 95% CI 1.16–1.67) and primiparous women with spontaneous onset of labor and emergency cesarean delivery (OR 2.69, 95% CI 2.26–3.19) [5].

In the present study, a statistically significant difference between both groups regarding amount of major primary postpartum hemorrhage. No women in carbetocin group required blood transfusion, while 14 (15.5%) in oxytocin group required blood transfusion and this difference was statistically significant (p50.05).

Additionally, the present study has shown that post- partum hemoglobin and hematocrit were significantly decreased 24-h postpartum in oxytocin group compared to pre-operative values, denoting more blood loss among oxytocin group.

In our study, none of the patient in carbetocin group required additional uterotonics while as high as 71.5% of women in oxytocin need additional oxytocin to insure adequate uterine contraction for long period. We do reach the same conclusions as many other who described a lower additional uterotonic need for treatment of uterine atony in women who took carbetocin soon after delivery [15].

Comparison of adverse events with carbetocin and oxyto- cin revealed that nausea, vomiting were significantly more common among oxytocin group with incidence rates ranged from 42.5% up to 67.5%. However, fever was reported among 20% of women in carbetocin group versus none in oxytocin group. All the reported side effects were tolerable and both drugs were shown to be safe.

We plan to conduct a larger study to verify our findings and to gather additional information. Our preliminary result showed that a single IV carbetocin of 100 mg was show to be more effective than a continuous IV infusion of oxytocin in maintaining adequate uterine tone and in preventing post- partum bleeding in obese nulliparous women undergoing emergency Cesarean delivery, both has a similar safety profile.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

1. Sterweil P, Nygren P, Chan BK, Helfand M. System 1. ACOG. ACOG Practice Bulletin: Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetrician-Gynecologists Number 76, October 2006: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol 2006;108:1039–47.

2. Lewis G, editor. CEMACH. Why Mothers Die 2003–2005— Seventh Report of the Confidential Enquires into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. London: RCOG Press; 2007.

3. Knight M, Callaghan WM, Berg C, et al. Trends in postpartum hemorrhage in high resource countries: a review and recommen- dations from the International Postpartum Hemorrhage Collaborative Group. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009;9:55.

4. Heslehurst N, Simpson H, Ells LJ, et al. The impact of maternal BMI status on pregnancy outcomes with immediate short-term obstetric resource implications: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2008;9: 635–83.

5. Al-Zirqi I, Vangen S, Forse ́n L, Stray-Pedersen B. Effects of onset of labor and mode of delivery on severe postpartum hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;201:273.e1–9.

6. Blomberg M. Maternal obesity and risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118:561–8.

7. Wedisinghe L, Macleod M, Murphy DJ. Use of oxytocin to prevent haemorrhageat caesarean section–a survey of practice in the United Kingdom. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2008;137:27–30.

8. Ozumba BC, Ezegwui HU. Blood transfusion and Caesarean section in adeveloping country. J Obstet Gynecol 2006;26:746–8.

9. Bergholt T, Lim LK, Jorgensen JS, Robson MS. Maternal body mass index inthe first trimester and risk of cesarean delivery in nulliparous women inspontaneous labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007;196:163.e1–5.

10. Zhang J, Bricker L, Wray S, Quenby S. Poor uterine contractility in obese women. [see comment]. BJOG 2007;114:343–8.

11. Fyfe E, Anderson N, North R, et al. Risk of first-stage and second- stage cesarean delivery by maternal body mass index among nulliparous women in labor at term. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117: 1315–22.

12. Combs CA, Murphy EL, Laros RK Jr. Factors associated with postpartumhemorrhage with vaginal birth. Obstet Gynecol 1991; 77:69–76.

13. Driessen M, Bouvier-Colle M-H, Dupont C, et al. Postpartum hemorrhage resulting from uterine atony after vaginal delivery: factors associated with severity. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117:21–31.

14. McDonald SJ, Prendiville WJ, Blair E. Randomised controlled trial of oxytocin alone versus oxytocin and ergometrine in active management of third stage of labour. BMJ 1993;307:1167–71.

15. Attilakos G, Psaroudakis D, Ash J, et al. Carbetocin versus oxytocin for the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage following caesarean section: the results of a double-blind randomized trial. BJOG 2010; 117:929–36.

16. Borruto F, Treisser A, Comparetto C. Utilization of carbetocin for prevention of postpartum hemorrhage after cesarean section: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2009;280:707–12.

17. WHO. Managing complication in pregnancy and childbirth: a guide for midwives and doctors. Geneva: WHO: 2000. Reprint 2007. Available from: http://www.whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/ 9241545879_eng.pdf [last accessed 27 Oct 2013].

18. Drife J. Management of primary postpartum haemorrhage. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1997;104:275–7.

19. Magann EF, Doherty DA, Briery CM, et al. Obstetric character- istics for a prolonged third stage of labor and risk for postpartum hemorrhage. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2008;65:201–5.

20. Kumari P, Gupta M, Kahlon P, Malviya S. Association between high maternal body mass index and feto-maternal outcome. J Obes Metab Res 2014;1:143–8.

21. Fyfe EM, Thompson JMD, Anderson NH, et al. Maternal obesity and postpartum haemorrhage after vaginal and caesarean delivery among nulliparous women at term: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012;12:112.

22. Doherty DA, Magann EF, Chauhan SP, et al. Factors affecting caesarean operative time and the effect of operative time on pregnancy outcomes. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2008,48:286–91.