Carbetocin for the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta- analysis of randomized controlled trials

Bohong Jin, Yongming Du, Fubin Zhang, Kemei Zhang, Lulu Wang & Lining Cui

Abstract

Objective: To compare the efficacy and safety profile of carbetocin with other uterotonic agents in preventing postpartum hemorrhage.

Methods: PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus and EBSCOhost were searched for relevant randomized controlled trials published until September 2013.Results: Carbetocin was associated with a significantly reduced need for additional uterotonic agents (RR1⁄40.68, 95% CI: 0.55–0.84, I21⁄44%) compared with oxytocin in women following cesarean delivery. However, with respect to postpartum hemorrhage, severe postpartum hemorrhage, mean estimated blood loss and adverse effects, our analysis failed to detect a significant difference. Studies comparing carbetocin with syntometrine in women undergoing vaginal delivery demonstrated no statistical difference in terms of risk of postpartum hemorrhage, severe postpartum hemorrhage or the need for additional uterotonic agents, but the risk of adverse effect was significantly lower in the carbetocin group.

Conclusions: Carbetocin has been associated with a similar low incidence of adverse effects to oxytocin and at least as effective as syntometrine and may become an alternative uterotonic agent for the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage. Further studies should be conducted to determine the safety and efficacy profile of carbetocin in women with cardiac disorders and to analyze the cost-effectiveness and minimum effective dose of carbetocin.

Keywords

Carbetocin, meta-analysis, postpartum hemorrhage, systematic review, uterotonic agent

History

Received 29 September 2014 Revised 19 December 2014 Accepted 22 December 2014 Published online 12 January 2015

Introduction

Traditionally, PPH has been defined as blood loss in excess of 500mL after a vaginal birth, and over 1000mL after a cesarean delivery. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has recommended that different criteria are used in the diagnosis of PPH. These include a hematocrit drop of greater than 10%, need for blood transfusion, and hemodynamic instability.

The most frequent cause of PPH is uterine atony, therefore, active management of the third stage of labor, particularly

the prophylactic use of uterotonic agent can significantly decrease the incidence of hemorrhage compared with expect- ant management [5,6]. The prophylactic medications cur- rently used are mainly oxytocin and syntometrine (a mixture of 5 IU oxytocin and 0.5 mg ergometrine). This mixture combines the rapid onset of oxytocin and sustained uterotonic effect of ergometrine. Although prophylactic use of syntome- trine in the third stage of labor is effective in reducing blood loss and PPH, cardiovascular and gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea, vomiting and raised blood pressure are considerably higher mainly due to stimulation of smooth muscle contraction and vasoconstriction by ergometrine [7], therefore, syntometrine is contraindicated in women with co-existing medical conditions such as cardiac disease, pre- eclampsia. These women are then administered oxytocin which is less effective in the prevention of PPH.

Administration of prostaglandins such as misoprostol and carboprost has been explored for several years. The use of misoprostol for the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage demonstrates lower effect than injectable uterotonic agent following vaginal delivery and is associated with a higher incidence of severe PPH and additional uterotonics [8]. These factors deem misoprostol unsuitable prophylactic agent for the prevention of excessive bleeding. Among the other agents that have been explored for the prevention of PPH, carbetocin appears to be a promising medication [9].

Carbetocin is a long-acting synthetic analogue of oxytocin that can be administered as a single dose injection in the route of intravenous or intramuscular. In pharmacokinetic studies, intravenous injections of carbetocin produced tetanic con- tractions within 2 min, followed by rhythmic contractions for a further hour. Intramuscular injection produced titanic contractions within 2 min, lasting about 11 min, and followed by rhythmic contraction for an additional 2 h. In comparison with oxytocin, carbetocin produces a prolonged uterine activity when administered postpartum, with respect to both frequency and amplitude of contractions [10]. Carbetocin is well tolerated and the safety profile is similar to that of oxytocin [11,12]. We reviewed relative studies regarding this subject and conducted a meta-analysis comparing the efficacy and safety profile of carbetocin in the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage following cesarean or vaginal deliv- ery with conventional uterotonic agent among women with high- or low-risk factors.

Methods

Search strategy

The systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines. We searched medical databases PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus and EBSCOhost for relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The search strategy was carried out based on the following combination of medical subject heading (MeSH) terminologies and keywords: postpartum hemorrhage, carbetocin, uterotonics agent, cesarean section and vaginal delivery. The search was limited to human subjects but without language restriction in any process of our searches or study selection. Trials were excluded if they were quasirandomized or if they evaluated only the effect of carbetocin on postpartum hemorrhage without comparison with other uterotonics. Published abstracts alone were excluded if additional information on methodological issues and results could not be obtained. Manual cross-reference search of the reference lists of relevant primary studies and reviews was carried out to identify publications for possible inclusion. Unpublished data or abstracts were not included.

Study selection

We included all the randomized controlled studies that compared carbetocin with other uterotonic agents for the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage in women who under- went cesarean or vaginal delivery. Supplemental Digital Content S1 shows the flowchart demonstrating the search and selection process. The selection process retrieved 38 refer- ences in PubMed, 73 in Scopus, 40 in Web of Science and 13 in EBSCOhost. Of the 164 identified references, 147 did not match our selection criteria based on the review of their titles and abstracts conducted by two authors (YMD and BHJ). These two authors then independently reviewed the full texts of the remaining 17 references to determine inclusion. We excluded five studies after evaluation of the full papers. The most common reason for exclusion was non-RCTs. Finally, 12 studies were deemed eligible for inclusion. Any disagreements about results were resolved by consensus or arbitration by a third reviewer.

Data extraction

The following information was extracted from the studies by two authors (YMD and FBZ): author, year of publication, randomized participants, interventions (including uterotonic agents, doses and route of administration), mode of delivery, with or without risk factors, and outcome measures consisted of primary and secondary outcomes. From every study, we collected the number of participants with events and the total number of participants in the experimental and control groups. For continuous data, the meta-analysis was performed using mean and standard deviation (SD) of each group. If the required data were not adequate in the report, the author was contacted and asked for supplementary data. If the author did not reply, whenever possible, the data were transformed using different procedures. For studies reported only values of median, range or interquartile range, the mean and SD were estimated using the recommendation of Hozo et al. [13]. The risk of bias for each study was critically assessed using the recommended approach in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [14].

Statistical analysis

In analyzing the results of the clinical trials, dichotomous data were tested by calculating the relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Continuous variables presented in mean and standard deviation were used to derive a weighted mean difference (WMD). RR and WMD from individual studies were meta-analyzed using a fixed effects model or random effects model for analysis if significant heterogeneity was observed (I2450%). Heterogeneity was investigated graphically using forest plots and statistically using the I2 statistic to quantify heterogeneity between studies. If pooled estimated effects were shown to be heterogeneous, sub-group analysis would be conducted to investigate possible sources of heterogeneity. The meta-analysis compared the outcome measures of carbetocin versus other uterotonic agent in women following cesarean or vaginal delivery. Statistical analyses were performed using REVMAN 5.0 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK).

Results

Included studies

The systematic review revealed 12 RCTs [11,12,15–24], involving 2975 participants, published from 1998 to 2013. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of these studies, stratified according to the prophylactic uterotonic agents used and the mode of delivery. Eight studies compared carbetocin with oxytocin [11,12,15–20]; six were conducted on women who underwent cesarean section [11,12,15,16,18,19], one was for women following vaginal delivery and the remaining included participants undergoing vaginal delivery or cesarean section. Eight trials performed a single 100ug intravenous bolus injection of carbetocin, while the dose and route of administration of oxytocin varied across the studies. Out of the eight studies that compared carbetocin with oxytocin, three trials [15,17,19] recruited participants undergoing cesarean section with at least one risk factor for PPH (e.g. pre-eclampsia, previous PPH, gestational diabetes, fetal macrosomia, previous cesarean section, etc.) while two studies [12,18] enrolled women with or without risk factors for PPH.

Five studies comparing the use of carbetocin with syntometrine or oxytocin in women undergoing vaginal deliveries followed the same definition for postpartum hemorrhage which was illustrated in the ACOG practice bulletin: an estimated blood loss in excess of 500mL following a vaginal birth. While in six studies evaluating efficacy and safety profile of carbetocin versus oxytocin in women following cesarean section, no one clearly defined postpartum hemorrhage according to the ACOG practice bulletin that ‘‘a loss of greater than 1000mL following cesarean birth often has been used for the diagnosis’’.

For studies compared carbetocin with syntometrine, the standard doses of 100ug carbetocin and 1mL syntometrine were intramuscularly administered to all the participants undergoing vaginal delivery. Three of the studies [21,22,24] were performed on women with no risk factor for postpartum hemorrhage while one study [23] was conducted on women with risk factors including a history of blood transfusion or retained placenta, grandmultiparity, twin pregnancy, fetal macrosomia, polyhydramnios or prolonged labor.

The vast majority of studies included in this systematic review used the need for therapeutic uterotonics as the primary outcome except for one study published in 1998, in which perioperative blood loss was assessed and used as primary outcome variable. The need for additional uterotonics was used as the primary outcome variable as it was the most important clinical indicator of postpartum blood loss after delivery, and the decision for the administration of therapeutic uterotonics was decided by the obstetrician based not only on clinical estimation of blood loss but also on the diagnosis of uterine atony based on palpated uterine tone. Secondary outcome measures varied across studies mainly including the incidence of PPH and/or severe PPH, incidence of blood transfusion, EBL, uterine massage and adverse effects profile.

Quality assessment

Overall, methodological assessment of included studies was of good quality. Both random sequence generation and adequate allocation concealment were performed in eight out of 13 studies. Three studies did not clearly describe the method of randomization and three trials used a block randomization of two causing allocation concealment less effective. Blinding was fully conducted in eleven studies and only two studies did not completely demonstrate whether the personnel and participants were blinded to the intervention. Attrition and selective reporting bias was detailedly specified in six trials. Other sources of bias were mainly because the projects were benefited from pharmaceutical companies. The quality assessment of the selected studies is detailed in Supplemental Digital Content S2.

Meta-analysis

Carbetocin versus oxytocin

Eight studies compared carbetocin with oxytocin as uterotonic agent in women following cesarean section or vaginal

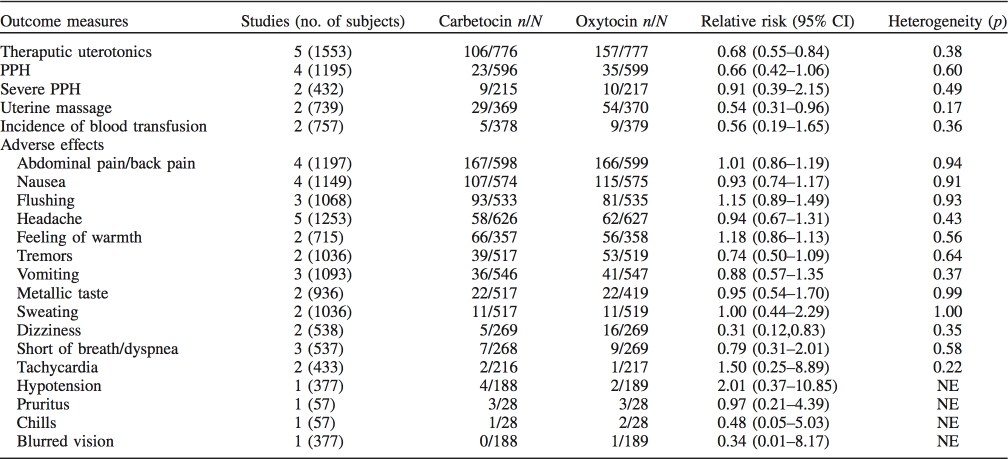

Table 2. Meta-analysis of outcome measures of studies comparing carbetocin with oxytocin in women following cesarean section.

NE, not estimable.

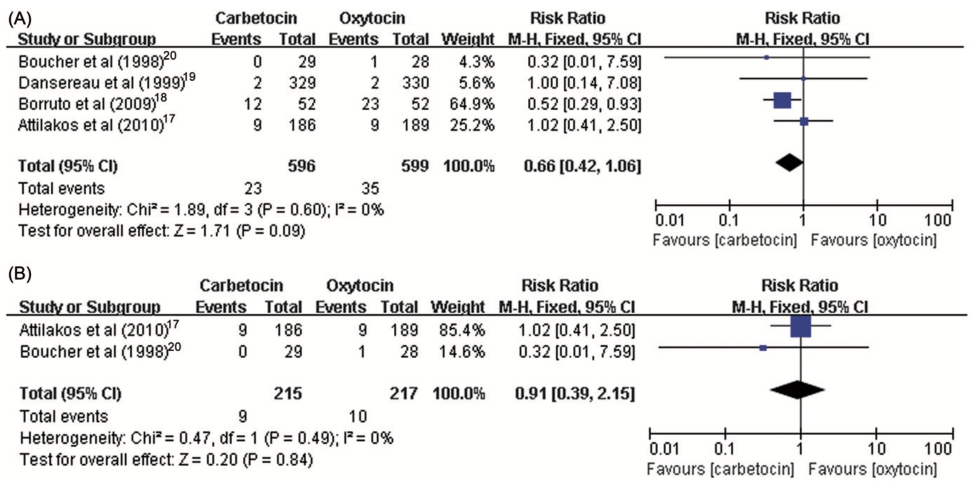

Figure 1. Forest plot showing the estimated effects of the incidence of (A) PPH and (B) severe PPH in women received carbetocin versus oxytocin following cesarean section.

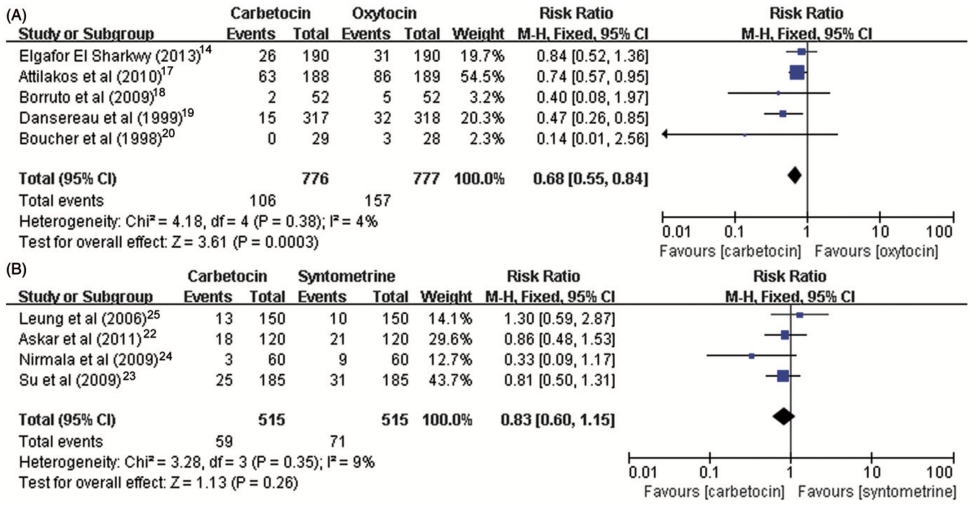

delivery. A standard dose of 100ug carbetocin was used across the studies while the total dosage of oxytocin varied from five to 32.5 units. Table 2 demonstrated the majority of the estimated effects of the meta-analysis for every primary and secondary outcome measure in women who underwent cesarean section. Most individual comparisons did not show interstudy heterogeneity. The risk of PPH was not signifi- cantly decreased with carbetocin compared with oxytocin (RR 1⁄4 0.66, 95% CI: 0.42–1.06, I2 1⁄4 0%) (Figure 1). However, carbetocin was associated with a significantly reduced need for subsequent interventions with additional uterotonic agent (RR 1⁄4 0.68, 95% CI: 0.55–0.84, I2 1⁄4 4%) (Figure 2) and uterine massage (RR 1⁄4 0.54, 95% CI: 0.31– 0.96, I2 1⁄4 47%). The pooled estimated effect showed that the risk of severe PPH (1000 mL or more blood loss in the third stage of labor) was of no difference between carbetocin and oxytocin groups (RR 1⁄4 0.91, 95% CI: 0.39–2.15, I2 1⁄4 0%). For the incidence of blood transfusion, all estimates of relative risk were less than unity but never reached significance.

The meta-analysis for adverse events observed in the carbetocin versus oxytocin group confirmed that the risk of experiencing nausea, vomiting, flushing, headache, feeling of

Figure 2. Forest plot showing the estimated effects of the incidence of (A) PPH and (B) severe PPH in women received carbetocin versus syntometrine following vaginal delivery.

warmth, tremors, abdominal/back pain, metallic taste, sweat- ing, short of breath or dyspnea, tachycardia, hypotension, pruritus, chills and blurred vision was similar in women following cesarean delivery, but except for dizziness (RR 1⁄4 0.31, 95% CI: 0.12–0.83, I2 1⁄4 5%) (Table 2). The adverse effects results of one study [15] were not included in the meta-analysis because the administration of small dose of misoprostol, which may increase the risk of adverse effects, limited the inclusion information into analysis.

For women following vaginal delivery, the incidence rate of PPH (RR 1⁄4 0.95, 95% CI: 0.43–2.09), the need for therapeutic uterotonic agent (RR 1⁄4 0.95, 95% CI: 0.43–2.09) and adverse effects were similar in comparison groups, while the need for subsequent intervention of uterine massage (RR 1⁄4 0.70, 95% CI: 0.52–0.94) was significantly reduced for the women receiving carbetocin compared with oxytocin (Supplemental Digital Content S3).

Supplemental Digital Content S4 showed blood parameters of carbetocin in comparison with oxytocin for women follow- ing cesarean section or vaginal delivery, the estimates of relative risk demonstrated that no significant differences with respect to mean EBL, hemoglobin level drop and uterine tone.

Carbetocin versus syntometrine

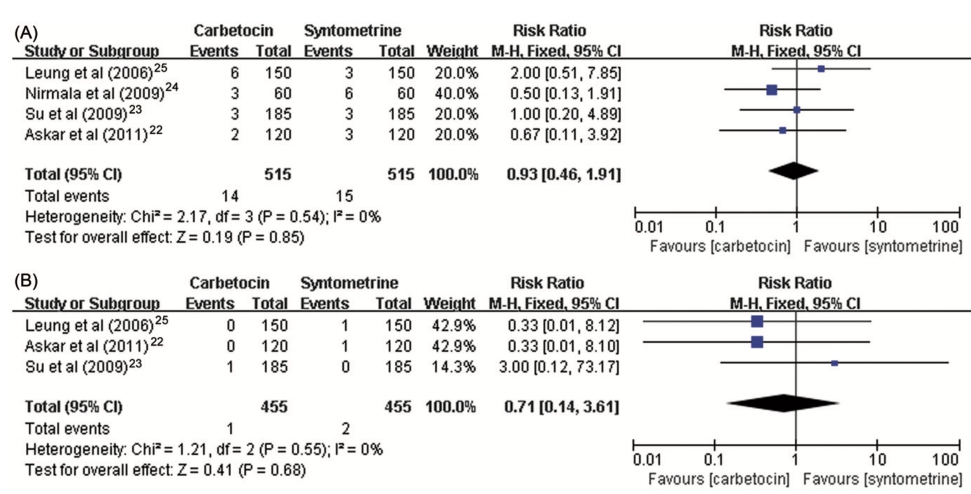

We analyzed a total of four studies comparing carbetocin with syntometrine in women who underwent vaginal delivery with the same dose of 100 ug carbetocin and 1 mL syntometrine and the same route of administration across all trials. Table 3 summarizes the estimates of relative risk for outcome measures of included studies. We recorded no significant difference with respect to the risk of PPH (RR 1⁄4 0.93, 95% CI: 0.46–1.91, I2 1⁄4 0%), severe PPH (RR 1⁄4 0.71, 95% CI: 0.14–3.61, I2 1⁄4 0%), the need for subsequent intervention of additional uterotonic agent (RR 1⁄4 0.83, 95% CI: 0.60–1.15, I2 1⁄4 9%), or incidence of blood transfusion (RR 1⁄4 1.75, 95% CI: 0.52–5.93, I2 1⁄4 0%) (Figures 2 and 3).

For adverse effects described in the four included studies, we observed increased incidence rates of signs and symptoms compared with the comparison of carbetocin versus oxytocin, e.g. nausea, vomiting and hypertension. For women who received carbetocin, they were much less likely to experience nausea, vomiting, sweating, tremors, retching and hyperten- sion. However, the estimate of relative risk of the outcome on tachycardia (RR 1⁄4 1.87, 95% CI: 1.01–3.47) for the compari- son between carbetocin and syntometrine groups was mar- ginally significant (Table 3).

Three studies [21,23,24] investigated the outcome of postnatal changes in blood pressure and/or incidence rate of hypertension at 30 and 60min in women who received carbetocin compared with syntometrine and two of them [21,24] resulted that there was a significant difference in the incidence rate of hypertension. Our meta-analysis found the same conclusion that women who received carbetocin were less likely to progress to hypertension (defined as blood pressure 140/90 mmHg) at 30 min (RR 1⁄4 0.06, 95% CI: 0.01–0.44, I2 1⁄4 0%) and 60 min (RR 1⁄4 0.07, 95% CI: 0.01– 0.54, I2 1⁄4 0%) after delivery compared to syntometrine. Two [21,23] out of the three studies reported that no significant difference was observed between the two groups as regards the increase in pulse rate at 30 and 60 min after delivery.

Supplemental Digital Content S5 showed the outcome measures of continuous data including mean estimated blood loss, hemoglobin level drop, length of hospital and pulse rate. We found that the WMDs between carbetocin and syntome- trine groups on estimated blood loss (WMD 48.84, 95% CI: 94.82, 2.85) and hemoglobin level drop (WMD 0.38, 95% CI: 0.35, 0.01) were less than zero and were statistically significant, but profound heterogeneity was seen between the studies.

Table 3. Meta-analysis of outcome measures of studies comparing carbetocin with syntometrine in women following vaginal delivery.

NE, not estimable.

Figure 3. Forest plot showing the estimated effects of the incidence of the need for therapeutic uterotonic agents of carbetocin in comparison with (A) oxytocin and (B) syntometrine.

Discussion

Our meta-analysis has shown that carbetocin was asso- ciated with a significantly reduced need for subsequent interventions with additional uterotonic agent and uterine massage compared with oxytocin in women who under- went cesarean section. However, with respect to PPH, severe PPH, mean estimated blood loss, hemoglobin level changes and the incidence of blood transfusion, our analysis failed to detect a significant difference. Furthermore, we recorded none of the adverse effects to be significantly different for the comparison between carbetocin and oxytocin groups in women undergoing cesarean section or vaginal delivery.

The estimated effects of studies comparing the carbetocin and syntometrine in women following vaginal delivery showed no statistically significant difference with respect to the risk of PPH, severe PPH and the need for additional uterotonic agent. However, women who received carbetocin experienced significantly fewer adverse effects and less blood loss.

One trial [25] from Mexico compared the cost- effectiveness of prophylactic carbetocin and oxytocin follow- ing cesarean section and found that the mean cost per woman was significantly lower following carbetocin treatment ($3525) compared with oxytocin treatment ($4054) (p50.01). Mean cost-effectiveness ratio for carbetocin was $3874, while for oxytocin was $4944. This was the first study discussing the issue but supplying no adequate data for analysis, more studies comparing the carbetocin with either syntometrine or oxytocin are needed for further investigation.

Reyes et al. [17] investigated carbetocin versus oxytocin in women with severe pre-eclampsia following vaginal or cesarean delivery and found that carbetocin was as effective as oxytocin in the prevention of PPH and had a safe profile which made carbetocin an appropriate alternative to oxytocin because it appeared not to have a major hemodynamic effect in women with severe PPH. Moertl et al. [16] specifically studied the hemodynamic effects of carbetocin versus oxyto- cin in women following cesarean delivery. The results showed that both uterotonics had comparable hemodynamic effects including heart rate, systolic/diastolic blood pressure and total peripheral resistance and demonstrated an acceptable safety profile for prophylactic use. Additionally, our meta-analysis of two studies found that women who received carbetocin were less likely to progress to hypertension after vaginal delivery compared with syntometrine.

The promising findings suggest that carbetocin has been associated with a similar low incidence of adverse effects to oxytocin and at least as effective as syntometrine and may become an alternative uterotonic agent for the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage in women undergoing cesarean or vaginal delivery. Although the findings show favorable data for carbetocin used in women with pre-eclampsia following cesarean delivery, further studies should be conducted to determine the safety profile of carbetocin treatment in women with hypertension or cardiac disorders. For the issues of cost- effectiveness and minimum effective dose of carbetocin required, more studies comparing the carbetocin with other uterotonic agent and different dosages are needed for further investigation.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

-

Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, et al. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet 2006;367:1066–74.

-

Carroli G, Cuesta C, Abalos E, Gulmezoglu AM. Epidemiology of postpartum hemorrhage: a systematic review. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2008;22:999–1012.

-

Thomas J, Paranjothy S. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Clinical Effectiveness Support Unit. National Sentinel Caesarean Section Audit Report. RCOG Press; 2001. Available from: http://www.ans.gov.br/portal/site/_hotsite_parto_2/ publicacoes/RCOG_2001_AC.pdf [last accessed 12 Feb 2013].

-

Cai WW, Marks JS, Chen CH, et al. Increased cesarean section rates and emerging patterns of health insurance in Shanghai, China. Am J Public Health 1998;88:777–80.

-

Begley CM, Gyte G, Devane D, et al. Active versus expectant management for women in the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;11:CD007412.

-

McDonald S, Abbott JM, Higgins SP. Prophylactic ergometrine- oxytocin versus oxytocin for the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;1:CD000201.

-

Carey M. Adverse cardiovascular sequelae of ergometrine. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1993;100:865.

-

Tuncalp O, Hofmeyr GJ, Gulmezoglu AM. Prostaglandins for preventing postpartum hemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;8:CD000494.

-

Chong YS, Su LL, Arulkumaran S. Current strategies for the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage in the third stage of labour. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2004;16:143–50.

-

Schramme AR, Pinto CR, Davis J, et al. Pharmacokinetics of carbetocin, a long-acting oxytocin analogue, following intravenous administration in horses. Equine Vet J 2008;40:658–61.

-

Boucher M, Horbay GL, Griffin P, et al. Double-blind, randomized comparison of the effect of carbetocin and oxytocin on intraopera- tive blood loss and uterine tone of patients undergoing cesarean section. J Perinatol 1998;18:202–7.

-

Dansereau J, Joshi AK, Helewa ME, et al. Double-blind compari- son of carbetocin versus oxytocin in prevention of uterine atony after cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;180:670–6.

-

Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005;5:13.

-

Higgins J, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from: http://www. cochrane-handbook.org/.

-

Elgafor el Sharkwy IA. Carbetocin versus sublingual misoprostol plus oxytocin infusion for prevention of postpartum hemorrhage at cesarean section in patients with risk factors: a randomized, open trail study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2013;288:1231–6.

-

Moertl MG, Friedrich S, Kraschl J, et al. Hemodynamic effects of carbetocin and oxytocin given as intravenous bolus on women undergoing caesarean delivery: a randomized trial. BJOG 2011; 118:1349–56.

-

Reyes OA, Gonzalez GM. Carbetocin versus oxytocin for preven- tion of postpartum hemorrhage in patients with severe preeclamp- sia: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2011;33:1099–104.

-

Attilakos G, Psaroudakis D, Ash J, et al. Carbetocin versus oxytocin for the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage following caesarean section: the results of a double-blind randomized trial. BJOG 2010; 117:929–36.

-

Borruto F, Treisser A, Comparetto C. Utilization of carbetocin for prevention of postpartum hemorrhage after cesarean section: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2009;280:707–12.

-

Boucher M, Nimrod CA, Tawagi GF, et al. Comparison of carbetocin and oxytocin for the prevention of postpartum hemor- rhage following vaginal delivery: a double-blind randomized trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2004;26:481–8.

-

Askar AA, Ismail MT, El-Ezz AA, Rabie NH. Carbetocin versus syntometrine in the management of third stage of labor following vaginal delivery. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2011;284:1359–65.

-

Su LL, Rauff M, Chan YH, et al. Carbetocin versus syntometrine for the third stage of labour following vaginal delivery-a double- blind randomized controlled trial. BJOG 2009;116:1461–6.

-

Nirmala K, Zainuddin AA, Ghani NA, et al. Carbetocin versus syntometrine in prevention of post-partum hemorrhage following vaginal delivery. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2009;35:48–54.

-

Leung SW, Ng PS, Wong WY, Cheung TH. A randomized trial of carbetocin versus syntometrine in the management of the third stage of labour. BJOG 2006;113:1459–64.

-

Del Angel Garc ́ıa G, Garcia-Contreras F, Constantino-Casas P, et al. Economic evaluation of carbetocine for the prevention of uterine atony in patients with risk factors in Mexico. Value Health 2006;9:A254.